How big is the constitutional challenge to the Obama health care law, which the Supreme Court will hear beginning today?

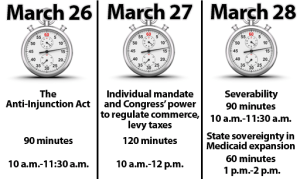

For starters, it’s big enough for the justices to schedule six hours of arguments — more time than given to any case since 1966. After all, the Affordable Care Act is arguably the most consequential domestic legislation since the creation of Medicare in 1965.

It’s also big enough to attract more briefs than any other case in history. At least 170, including more than 120 “friend-of-the-court” or amicus briefs, have been filed, many of which are joined by 10, 20 or more groups of every imaginable description.

And, finally, it’s big enough to cause the justices to postpone until October half of the 12 cases that they would ordinarily hear in April in order to clear time to get started on the health care opinions that they are expected to issue by the late June, or possibly, early July.

What’s it all about?

The immediate issues, in the order the court will hear them, begin with the question of whether the so-called “individual mandate” — which requires that almost all Americans without coverage buy individual health insurance policies or pay fines — is ripe for adjudication now. Or must the case be deferred until 2015 because of the 1867 Anti-Injunction Act, which bars federal courts from ruling on the constitutionality of tax laws before payments are due?

After that come the arguments about what many consider the central issue: whether the mandate, which is unprecedented, should be voided because it represents an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’ powers to regulate commerce and to levy taxes.

Next is what becomes of the law’s hundreds of other provisions, covering 2,700 pages, if the mandate is unconstitutional? Are some or all of them “severable,” meaning that Congress would have wanted them to stand even if the mandate falls? For example, what about the provisions establishing tax credits to help small businesses and individuals buy health insurance and taxing large employers that do not provide full-time employees government-approved coverage?

Apart from those issues, does the law’s expansion of Medicaid violate the sovereignty of the states by effectively requiring them to spend more of their own money or forfeit all of the federal Medicaid money they now receive?

What’s the likely outcome?

Nobody knows. It’s clear that the court’s four more liberal members, like almost all other liberal legal experts, will find the law constitutional in all respects. It’s also clear that conservative Justice Clarence Thomas will vote to strike down much or all of the law. It’s less clear what swing-voting Justice Anthony Kennedy and conservative Chief Justice John Roberts as well as Justices Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito will do.

Kennedy, Roberts, Alito, and (especially) Scalia — whom the government’s brief quotes five times — have all joined past decisions construing federal regulatory power very broadly. Two respected conservative federal appeals court judges, Laurence Silberman and Geoffrey Sutton, who is one of Scalia’s favorite law clerks, have upheld the law.

What are the major arguments for and against the individual mandate?

Defenders say that the broad constitutional power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce, and the even broader power to “lay and collect taxes,” both provide ample authority for requiring that people buy insurance as part of a comprehensive scheme to end “discriminatory insurance practices that have excluded millions of people from coverage based on medical history,” in the words of a brief by Solicitor General Donald Verrilli.

The same brief also asserts that uninsured people consume $43 billion a year worth of emergency-room and other health care for which they do not pay, costs that are shifted to insurers and that raise insured families’ average premiums by more than $1,000 a year. Critics of the law dispute these numbers.

The 26 states challenging the law (along with a business group and four individuals) say, in the words of a brief by Paul Clement, who was solicitor general under President George W. Bush: “The individual mandate rests on a claim of federal power that is both unprecedented and unbounded: the power to compel individuals to engage in commerce in order more effectively to regulate commerce. This asserted power does not exist. … It is a revolution in the relationship between the central government and the governed.”

Clement also stresses that President Barack Obama and his allies in Congress insisted during the debate before the measure became law that the financial penalty for failing to comply with the individual mandate is not a tax. They should not be allowed, he argues, to “enact legislation that would not have passed had it been labeled a tax and then turn around and defend it as a valid exercise of the tax power.”

The Anti-Injunction Act?

This reconstruction-era statute bars courts from considering the constitutionality of tax laws until payments are due. It will apply here if the court deems the individual mandate’s penalty provision a “tax.”

Because the mandate is not scheduled to take effect until 2014 and the first penalties would not be due until 2015, the federal courts would not yet have jurisdiction to consider the constitutionality of the penalties or the mandate. In other words, consideration of the case would be postponed until 2015, and, therefore, such a decision would convert the biggest case in decades into the biggest anticlimax in Supreme Court history.

Both sides say that the Anti-Injunction Act does not apply. But the court appointed a lawyer as “friend of the court” to argue that it does, as one federal appeals court held. This appointment signaled the court’s care to observe arguable limits on its jurisdiction even when the parties agree that it has jurisdiction.

What are the major arguments on severability?

The government says that if the court strikes down the mandate, it should defer until future cases any ruling on the severability of most other provisions. But, if it does rule on severability, the government maintains that only two other provisions should go down with the mandate. Those are the “guaranteed-issue” and “community-rating” provisions, which bar insurers from denying coverage or charging higher premiums because of medical history. Without the individual mandate, the government says, those provisions would send premiums soaring by creating incentives for healthy people to defer buying insurance until they need health care.

The 26 states argue that the mandate was deemed by Congress to be “necessary to make the other provisions work as intended,” and that the court should strike down the whole law.

The court appointed another friend-of-the-court lawyer to write a brief arguing that a decision striking down the mandate should leave the rest of the law — including guaranteed issue and community rating — intact.

What are the major arguments on Medicaid?

The government asserts that “it is well settled that Congress’s spending power includes the power to fix the terms on which it will disburse funds to the states,” that Congress has repeatedly expanded the state-federal Medicaid program, and that this new expansion will not “impose significantly onerous burdens on the states.”

The 26 states counter that the Medicaid expansion unconstitutionally coerces them because it “threatens States with the loss of every penny of federal funding under the single largest grant-in-aid program in existence — literally billions of dollars each year — if they do not capitulate to Congress’ steep new demands.”

Stuart Taylor, Jr. is an author and contributor to the National Journal and other publications.

> > For more on the Supreme Court’s decision on the health law, check out our resource page.