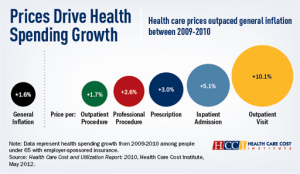

Higher prices charged by hospitals, outpatient centers and other providers drove up health care spending at double the rate of inflation during the economic downturn– even as patients consumed less medical care overall, according to a new study.

Prices rose at least five times faster than overall inflation for emergency room visits, outpatient surgery and facility-based mental health and substance abuse care from 2009 to 2010, says the report by the Health Care Cost Institute, a nonpartisan research group funded by insurers. Prices declined in only one category: nursing home care, which saw a 3.2 percent drop in the cost per admission.

One of the areas with the fastest growing spending, meanwhile, was children’s medical care.

“The story really does seem to be prices,” said Martin Gaynor, chair of the institute’s governing board and a health care economist at Carnegie Mellon University.

Representing one of the broadest looks at actual claim payments made by insurers, the study’s findings raise questions that go to the heart of the nation’s $2.6 trillion annual bill for health care: Why are prices for medical services rising far faster than inflation? Is a rapid increase in spending on children an anomaly, or a long-term trend with major implications for future costs?

“If you don’t know what the cause is, you don’t know what the right policy lever is (for a solution),” Gaynor says

He says the Institute, founded last year to make insurance industry payment data available to the public, will address some of those questions in subsequent research.

The findings are based on about 3 billion claims paid by Aetna, Humana and UnitedHealthcare on behalf of 33 million people with job-based insurance nationwide. The data represent about 20 percent of the people with insurance nationally, but do not include spending for people who are on Medicare, Medicaid or those who buy their own policies.

The report shows that people with job-based insurance “are paying more and getting less,” says Chapin White, a senior researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington. He did not work on the report.

Hospitals and other medical providers “just seem to be able to raise prices faster than general inflation,” he says.

Workers’ copayments and deductibles, which they pay on top of their share of premium costs, also rose, according to the study. Such “out-of-pocket costs” jumped 7.1 percent between 2009 and 2010 to an average of $689 per person.

Prices and overall use of medical care are major factors driving the cost of health insurance. While the study does not analyze premium increases, those have risen steadily, with one national employer survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation showing a cumulative 138 percent increase in job-based insurance premiums between 1999 and 2010. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

As part of the federal health law, all states last year began reviewing premium increases of 10 percent or more, requiring insurers to justify the increases. There are no similar national efforts to examine price increases by hospitals or other medical providers.

Insurers argue they are just passing along rising costs to consumers, keeping only a narrow profit margin and are often outgunned in contract negotiations by hospitals, many of which are “must-have” facilities in an insurer’s network.

“This is an important study that clearly demonstrates that rising prices for medical services are driving health care cost growth,” said Karen Ignagni, president and CEO of America’s Health Insurance Plans, the industry lobby. “Reducing medical costs is essential to making health care coverage more affordable for individuals, families, and employers.”

Researcher White says insurers must take a more active role. “If insurers are incapable of reining in growth of prices they pay providers, that’s a problem,” he says.

Struggling with rising costs, some states and insurers are looking at new approaches. In Massachusetts, for example, supporters and opponents are sparring over a proposal that would impose financial penalties on hospitals or other providers who exceed by 20 percent or more a specified state median for a medical service.

In North Carolina, one major insurer aims to negotiate contracts with hospitals and other medical providers that limit increases to no more than the medical inflation rate.

“We have met that goal for the past two years,” says Brad Wilson, CEO of Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina. That effort, along with lower use of medical services, translated into zero to 5 percent premium increases for policies sold to individuals — the smallest rise in five years.

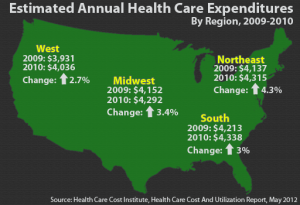

The report found the biggest spending increases in the Northeast, up 4.3 percent and – surprisingly — among children under 18, up 4.5 percent nationally. That compares with a 3.1 percent jump in spending on 55 to 64 year olds. While spending grew fastest among pediatric patients, the report found medical care for older patients costs more in total dollars – averaging $8,327 a year – than for those under 18, at $2,123.

A future report will probe the reasons for the growth in pediatric spending. Possibilities could include big expenses for premature babies, the rising incidence of obesity and related diseases or an increasing demand for mental health and behavioral services.

It could also reflect families’ increasing struggle to pay their share of medical costs by foregoing or delaying medical visits for their children, says Irwin Redlener, a professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and president of the Children’s Health Fund, a nonprofit that provides medical care to underserved children.

“Even families with employer-based insurance are seeing their costs going up , but not their salaries,” says Redlener. So they may be “saving where they can” and foregoing preventive care, such as vaccinations, and treatments for chronic illnesses, such as asthma or diabetes.

Overall, during the period analyzed, prices charged nationally grew the most for emergency room visits, up 11 percent, surgery that did not involve a hospital stay, up 8.9 percent, and mental health and substance abuse services, up 8.6 percent.

The price per hospital admission rose an average of 5.1 percent, hitting $14,662. Surgical admissions had the highest overall price tag, at an average of $27,100, representing a 6.4 percent increase from 2010.

Spending by insurers and policyholders on medical care rose 3.3 percent per person from 2009 to 2010, about twice the 1.6 percent increase in the Consumer Price Index.

Mary Agnes Carey contributed to this story.